ITHAKA LOG

CRUISING WORLD

Characters In Kuna Yala

By Bernadette Bernon

Kanildup, San Blas, Kuna Yala, Panama

09° 28.900′ North 078° 38.200′ West

On one of our first days in the San Blas, a 20-foot-long dugout, made from one huge tree, and propelled by an outboard rather than by sails, arrived gently alongside Ithaka. A young man was driving. Aboard with him was a pretty Kuna woman selling molas. As we tied fenders between Ithaka and the ulu, the woman offered us a regalo (gift, in Spanish) of three perfect avocados and held up an intricate mola she’d made. Impressed, we invited her aboard to look at her work. She spoke to her ulu driver in Kuna, then introduced herself to us in fluent Spanish, telling us that she lived on Sidra, a Kuna island nearer the mainland.

Lisa Harris, master mola maker.

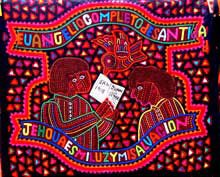

When she heard what language we were speaking, she switched to English “My name is Lisa Harris,” she said. “I’m a Master Mola-maker.” She was indeed. Her molas are gorgeous: intricate pieces of reverse-appliquéd fabric — three, four, and five layers thick — then embroidered over in minuscule stitches. The designs are sophisticated, and not a stitch showed anywhere where the fabric is sewn back in hundreds of places. Right away, I knew I was going to own a couple of these pieces of art before the morning was through. Then, as Douglas and I narrowed down our favorites, it hit me.

Lisa Harris. I knew the name.

Detail of one of Lisa’s more intricate and expensive molas.

Lisa is indeed a master mola maker and is known as one of the best in the San Blas — we’d heard that her special molas commanded higher prices than all others. We’d also heard that she was a transvestite. Cruisers who’d passed this way before us had told us about her. Not since Steve Colgate stopped by Ithaka one day for lunch in Newport have we had such a celebrity on the boat.

“Lisa!” I said (after we’d finished negotiating for three molas). “We’ve read about you and heard about you. You’re famous.” Not unaccustomed to attention, she beamed.

“I am the best,” she smiled demurely. Not a brag — just a fact.

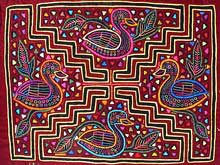

Lisa’s hummingbirds.

Mola making is a critical part of every Kuna family’s livelihood. Mothers begin teaching their daughters to make molas when the girls are young — you see many simple little coaster-size molas made by kids who are starting out in the craft, and their mothers often try to sell one or two of them for a dollar, or they’ll give you one as a gift if you give them the gift of some food — coffee, dried milk, sugar. By the time they’re teenagers, girls are making the real articles and going out with their mothers on the ulus to market them to passing boats. We’ve heard it told that in Lisa’s immediate family — a clan that had a heritage of famous mola masters — there were no daughters, so she was brought up as a girl, and taught by her mother the sewing skills of a woman. Today, she looks and dresses entirely feminine.

This close-up photo shows the tightness of the stitching on the reverse appliqué technique.

Douglas and I are thrilled with the molas we bought from Lisa, have enjoyed her company and getting to know her. We’ve seen her many times since that first day, tearing around in her ulu. When she sees us, she always waves and peels over to Ithaka to chat for a while. She’s taught us what makes a top mola, and she’s told us about her family, about Kuna customs, myths, and icons that are often part of many of the designs we’ve been seeing in the work of other mola makers. She told us how every master mola maker must select one person she feels is capable of learning this skill at a high level, and then spend years teaching her everything the master knows. Lisa’s grandmother selected Lisa’s mother. Lisa’s mother selected Lisa. Lisa has selected a niece, whom she tutors every day. In addition to tutoring and making her own molas — she says she averages six molas every four months, working from one to another simultaneously — she goes around the islands selling them herself. Considering that she can speak English and Spanish (each self-taught) she’s her own best salesperson.

Meeting Lisa was way cool, as my little sister Kelli would say. Lisa’s a major character in the San Blas, a working girl who supports her mother. But now that we’ve been here awhile ourselves, we notice that the place hosts lots of full-fledged characters who thrive on the freedoms and remote beauty of this still somewhat wild place.

Many Kuna women are now using blue fabrics in their molas because tourists like them. However, the traditional colors preferred by the Kuna for their own molas are deep reds.

In a small mainland Kuna village, we met Pedro, a schoolteacher. He’d come from Panama City, a sophisticated place full of museums, high-rises, medical centers, malls, cultural events, colleges and university, to accept a four-year government contract to teach English in this Kuna settlement. He’d jumped at the opportunity, he said, as the teaching market in the city was saturated, and he’d been desperate to find a full-time position with benefits. Now he’d been teaching at the settlement for a year and was absolutely miserable. The Kunas, who guard their autonomy with a passion, and seem determined to keep their bloodlines “pure,” had their own unwritten laws for how Pedro should live among them. He’s allowed to socialize with the Kunas only on a very limited basis. But he was not, under any circumstances, allowed to socialize with the Kuna women. If he was caught speaking with a Kuna woman alone, she and he would be called before the saila (village chief) and he would be fined hundreds of dollars. If he was caught again, the fine would be tripled and he would risk losing his job. Oddly, he was not allowed to eat in any public place with “white” people. This, he told us, is so that he won’t negatively influence the gringo tourists. (After years of oppression at the hands of the Panamanians, Kunas don’t seem to like or trust them on principal, even if the person in question is a professional schoolteacher living and working among them.)

Photo: Marty Baker

It has to happen. The influence of the modern world seeps in even to Kuna Yala.

After we’d met Pedro earlier in the day, Douglas and I had invited him to join us for some chicken at a little two-table Kuna dive in the settlement. “Watch this,” he said with disgust, when the proprietor brought our three meals out. His was put on another table. We started to protest, but he shushed us. “Don’t bother,” he said, rolling his eyes. “If I don’t move over there to eat it, I’ll be called in front of the saila tomorrow morning. It’s not worth fighting it. This is their Kuna Yala, and they want to keep their damn purity. So to hell with them. I’ll just keep to myself and do a lot of heavy drinking to get through this next two years. When it’s over, I’ll get my ass transferred back to the city.” We left Pedro sitting there dejectedly, his face florid with alcohol, gulping back the night’s tenth beer.

Kuna women are proud of their thin legs, and accentuate them by wearing anklets made of hundreds of beads. They do the same on their wrists.

But not all characters are locals. One peaceful day here, just north of Banedeup, in the remote reaches of Kuna paradise, we saw an astounding apparition. Preceded by an elegant dinghy marking the trail and watching for shallows, a 95-foot Dutch-built Jongert sloop pulled into the cove where we were anchored. After so many months away from “civilization,” Douglas and I were stunned to see a sparkling large yacht so close and dwarfing us. (Our mast didn’t even reach as high as the first set of their four levels of spreaders.) We just gaped at it as the dinghy driver joined the other three people on board, settled their anchor and they puttered around on deck. Not long afterward, a young woman climbed into the inflatable and headed over to Ithaka.

“Hello!” she said. “We just came through the Panama Canal. We’re heading north, and I was wondering if you have a schedule and frequencies for Caribbean weather faxes on the HF?” (High Frequency of SSB radio.) She was French, pretty and bubbly, and wanted to chat in a big way.

“Sure! Come aboard,” I said. “Have some lemonade while we write it down for you.”

“Oh, wish I could, but I can’t,” she said, glancing over her shoulder to the other boat. “They’ll see me and think I am having a good time.”

“They?”

Photo: Marty Baker

“The owners. They’re driving me absolutely crazy. We just spent the last year sailing 30,000 miles around the world. Rush. Rush. Rush. We sailed all the way down to Antarctica, and spent only two days there! We spent one day in Patagonia. We’re only spending one day, today, in the San Blas. They get bored if we stay anywhere longer. Every day I have to call her madam and him sir, and iron all their clothes, clean, and present three formal full-course meals. My boyfriend is the captain. It’s just the two of us running the boat. There’s no ventilation below, and they don’t like to put on the air conditioner. I’m going mad!”

Jeez.

“Well,” said Douglas, “after dinner, when they go to bed, sneak over for a coffee or a nightcap with us.” She was so thrilled, you would’ve thought he’d tossed her a life ring.

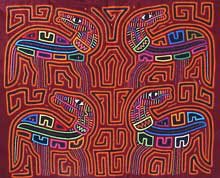

Four Ducks All In A Row.

Helène and Jean arrived at 9:30 that night, and we kicked back. They had their own cruising boat, an old Alden 40, on which they’d been cruising for a few years. They learned about the two professional crew positions on the Jongert and that the boat was going to the Antarctic. Always dreaming of exploring such a destination under sail but never imagining that they’d be able to go there on their own boat, they took the jobs as captain and first mate/cook on the 95-footer, left their boat on the hard in South Africa, and set off. A whirlwind year of offshore sailing and whistle-stop tours awaited them. We all laughed and chatted into the night, about sailing and traveling, and money, about how it’s a challenge to get the mix and pace of all three quite right. But we all agreed how crazy their voyage sounded.

The next morning, at first light, we heard an anchor chain being raised. We climbed up on deck and waved to Helène and Jean — both outfitted in their pressed uniforms — and wished them the best. Two weeks later, we received an e-mail from them. They’d arrived in Miami, having completed in 10 days their cruise of the entire southwest and northwest Caribbean, an area that had taken us two years to travel.

This is one of my favorite molas. A clean design, beautifully executed, of four horses.

We’ve met some very entrepreneurial Kunas, who travel miles and miles in their ulus, out to where the cruising boats are anchored, offering to do our laundry or go to the mainland to buy groceries. On the mainland, we met Federico, a jolly Kuna man who’s plugged in to everything a cruiser may want or need in Nargana. On top of his hut, he has a tattered flag that once said, he claims, “Yacht Services.” Federico found us diesel and transported it out to Ithaka. His wife did our laundry, he walked us around town to show us who was making the best bread, who had the best vegetables, the freshest fish, where we could make phone calls. He took us on an entertaining voyage in his ulu up the Río Corazón de Jesus where we collected fresh water in our jerry jugs when our tanks were getting low, where we swam in the cool running river, and then on the way back he stopped and we picked dozens of perfect golden mangos from the trees along the river’s banks. All the while, Federico, in a mix of wild gesticulations, Spanish, facial gyrations and some English, entertained us with Kuna history. When we ordered a new windlass motor from the States and had it shipped to Panama City, the agent we hired there to handle the transfer to the San Blas screwed up, and had it dropped off at the airstrip in Nargana, where there’s no terminal. Ahhh! When we found out about the error, long after we’d sailed on from Nargana, we hustled Ithaka back there, a one-day sail, and as we puttered into the harbor and dropped the anchor, there was Federico, heading for us and beaming, our windlass motor in the front of his ulu.

Christmas shopping in Kuna Yala.

We’ve met scraggly characters in the San Blas who’ve been cruising out here among the islands for years on end, many of whom have never even officially checked into Panama. Nobody comes out to check. Kuna Yala is a different universe than official Panama, and everyone, especially the cruisers and the Kuna, seem compelled to keep it that way.

The most interesting characters we’re meeting out here continue to be the Kuna women with whom we come in contact almost daily. Most of them are very shy, but polite. They’re proud women, and they just want the chance to show you their amazing work. They don’t ask much money for their molas — anywhere between $5 and $20 each, depending on quality (although some of Lisa’s can be several times that). Sometimes, as you’re anchoring, and preoccupied with the task at hand, it’s easy to become annoyed as ulus crowd around your boat, even before your hook is in the water. But if you wave them away politely and ask them to come back later, they’ll wait a ways off, hovering for the signal that its OK to resume their marketing efforts.

An ulu pulls up to Ithaka, and the women of East Lemon Cay show Bernadette their molas.

Once you smile and wave, they’ll paddle up and stay alongside your boat for as long as it takes for you to admire their buckets full of molas, and admire their children, who are usually in the ulu with them. They’ll do their best to explain, in Spanish, what each mola means to them — after all, the inspirations for these varied geometric and realistic designs come out of each of these women’s heads. Every mola, like a response to a Rorschach card, exposes the woman’s imagination, how her gray matter interprets her world.

Lisa, with her mola of a medicine woman.

Often, the Kuna women ask us for “revistas, por favor?” They love to see magazines, which give them new ideas for new images for their molas. Often, I’ve wished we’d brought down some old National Geographics, or art magazines — something inspirational, but not junky. Or maybe not. In their efforts to be more commercially successful, some women have incorporated some distinctly non-Kuna icons. We’ve actually seen molas with Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and in a particularly jarring cross-cultural calamity, a magnificent mola depicting three Teletubbies, which Douglas bought for a particularly idiosyncratic friend of ours. So, maybe it’s better if they just continue doing their craft as they are — an entire population of women, almost every one of whom is expressing her wildest imagination in molas.

Kuna women, in the dramatic native costumes and beads they wear every day, are extremely photogenic. But they are particularly put off by cameras aimed their way. If they see a camera, they often cover themselves completely in the plastic sheets they use to protect themselves from spray and rain in their ulus. Often they ask for a dollar if you want to take their picture, because a saila on one island once saw a postcard of a Kuna woman for sale on the mainland for a dollar. Annoyed that Panamanians and others were profiting off his people, he decreed that a dollar was also a fair price for a photo, so the Kuna, too, would get something out of the experience.

If you buy a mola, however, shyness begins to disappear. Usually you’re enthusiastically invited to dinghy ashore to visit the woman’s family on the island. Often, you’re welcome to take a couple of photos of the woman who made your mola. Then suddenly, they get shy again, giggle, and paddle away. Except for the greatest character of all, of course. Lisa. When we asked if we could take her picture, she took out her compact and lipstick, and checked her makeup, ready for her close-up.

Chartering in the San Blas

For sailors wishing to charter a boat in the San Blas archipelago, there are two options. Both are crewed, and both are excellent value. (There’s no bareboat chartering allowed in the San Blas.) Getting here is easy; fly into the international airport at Panama City, then connect by smaller airlines that service the outer islands into the larger Kuna towns of Porvenir, or Nargana, or any of several other choices along the mainland coast. Meet your charter boat there, and off you go! We’ve checked out the following opportunities:

San Blas Sailing

This company is the only one organized and legallyoperating out of the San Blas islands as a regular year-round business. We spent an evening with the president of the company, Jean Charles Cuissard. JC had a chartering couple on board for a week who were celebrating their honeymoon, and we all shared a delicious dinner together, compliments of the skipper–a great chef.

San Blas Sailing specializes in charters from 3 to 21 days, explorations of the reefs and some of the 368 islands, visits to remote Kuna Yala villages, snorkeling, fishing, and kayaking. (All this equipment is onboard.) Also available several catamarans, which also charter on the west coast of Panama, and on which guests can do a Panama Canal Transit. Here’s how to contact San Blas Sailing, which has their booking office in Panama City:.

Tel: (507) 314-1800 . Website: www.SanBlasSailing.com.